|

| Link |

To

read deeply and dynamically means, among other things, to embrace the exciting

fact that each new book defines its own terms and offers its own rules for

reading itself. A good man in Hamlet is different than a good man in The Importance of Being Ernest, for

example. Heroism in The Iliad is dynamically different that heroism in The Things They Carried. And so is the case with this complex,

mysterious poem. Our first job is that

we need to learn each book's own rules. What are the rules, the 'operating manual,' for Beowulf?

On

the first page of Beowulf, we know quite a bit. We know, for example, the poem’s

definition of a good king (god cyning),

one who has gifts in his hand for his kin and a bloody sword in his hand for

his enemy. We know that a person’s identity

is inextricably bound to the behavior of his lineage before him. No one is “his own man;” his identity, as a

result, is largely out of his control. We know the leader of the Danes - Hrothgar - embodies the kingly traits of warrior par

excellence and generous gift-giver as defined in the poem.

As

the pages continue and we learn of Hrothgar’s many successes, we learn about

the poem’s definition of a villain. We

meet Grendel and we are given a dynamic portrait of evil, the “good king”

flipped on its head.

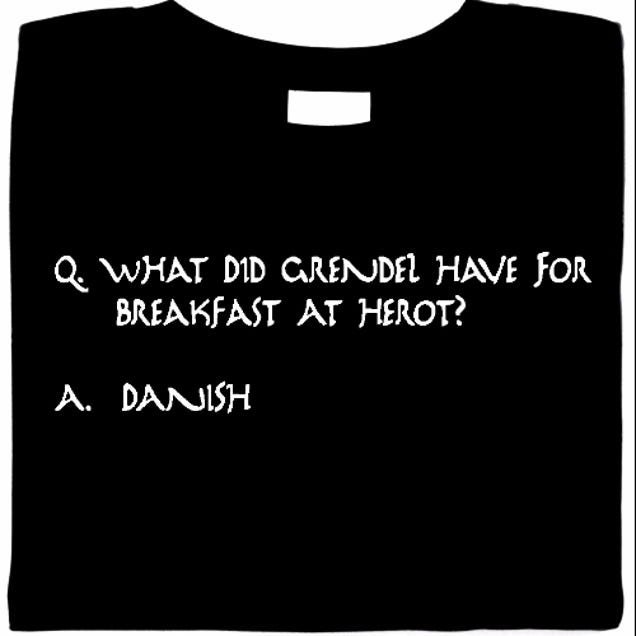

Literally

speaking, Grendel is the monster that has decimated the Danes’ mead-hall and

gruesomely killed many of their best men.

Grendel only lives for about 20 pages (yet ravages the mead hall for

over a decade) but he is as interesting as any villain created in the last 100

years. He is not merely a “monster” as

he is often called in translation. He is

in Caines cynne (“in the line of Cain”

- l. 107) and is thereby genetically connected to the father of weapons,

murder, and fratricide. The Cain

connection is essential here, making Grendel the worst nightmare this poem can

conjure because kin-killing is in his DNA.

In this poem, warriors needed to utterly trust in the loyalty of their

fellow warriors and their kin.

Breakdowns in this system did not lead to a psychological insecurity but, rather, death itself. Grendel is also

an Ellen-gaest (86) or a

“powerful demon” or “powerful stranger.”

He moves like a villain and is called Earfothlice (86) – a prowler. He is Feonde on helle (100)–a fiend/enemy out of hell (a place as real to this poem's audience as Boston or New York is to us!). Grendel is Eotonas (112) – an Ogre, the Old Norse creature who was the giant, monstrous

undead, human but larger and cannibalistic.

He was preternaturally huge (gigantas

– l. 113) and, perhaps most disturbing of all was that he was an Orcneas (112), an evil phantom (from Old

Norse “ne” – corpse, eotenas “to eat” – hence “corpse eater”

– later reformed into Tolkien’s “orc”).

And the true sign of Grendel’s evil (as if corpse-eating wasn’t enough!)

is that Grendel lives out the most horrifying of Anglo-Saxon fates. He is alone, an An-gengea (165) – literally “one who goes alone” or “solitary one.” All of this information lives on a couple

pages in the poem and describes just one of the poem’s three key villains. We know his spiritual lineage and his

solitude, his size, his diet, and even how he moves, each of these details

adding another layer of evil to an already self-evident villain.

In

just a handful of manuscript pages, lines are being drawn. We know the poem’s standard for a good king

and also for the objective villain. At this

point, any rational reader would occasionally glance at the cover of the book

and wonder, where is the title character?

When

we finally meet Beowulf, we are not given the depth of information that we get

with the good king or the murderous monster.

In the first quarter of the

poem, we meet Beowulf, hear him speak persuasively and see him fight and behave

like a hero.

But unlike most narratives in which the hero has the

deepest backstory, Beowulf, who has the strength of 30 men in each arm, remains

a mystery. He tells heroic tales of his

youth that are uncorroborated. We know

his father’s name but he has no wife, no children, and his king has

mysteriously let him go on this strange search-and-destroy mission on behalf of

another people. Beowulf has no authority

and deep lineage (like King Hrothgar) and no nuanced personality and set of

traits (like Grendel).

Beowulf finally identifies himself to the Danish

coast guard when he bluntly states, “Beowulf

is min nama” (“Beowulf is my name”). I can’t help but to wonder that the poet had a clear understanding of

what made a good king and a convincing villain but perhaps didn't exactly know what to make of this Beowulf. Or maybe this is an early

example of the poet wanting the auidence to create its own definitions along the

way, to help shape the poem in the listening. The poet of the mead-hall was called the ‘shaper’ (scop) after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment