When

I was a little boy, my friends and I would play “Star Wars.” We would take turns being either Luke

Skywalker and Han Solo or the villains Darth Vader and the Storm Troopers. Even though we were five, we innately

understood the rules of the game. Good

guys were noble, loved flying in land-speeders and space ships and enjoyed

employing their favorite catchphrases at critical moments (“May the force be

with you!”). Darth Vader breathed

heavily and had magical powers while the faceless Storm Troopers killed

anything that moved (and, fortunately, had atrocious aim!). But we understood the rules of the game and

there was no ambiguity.

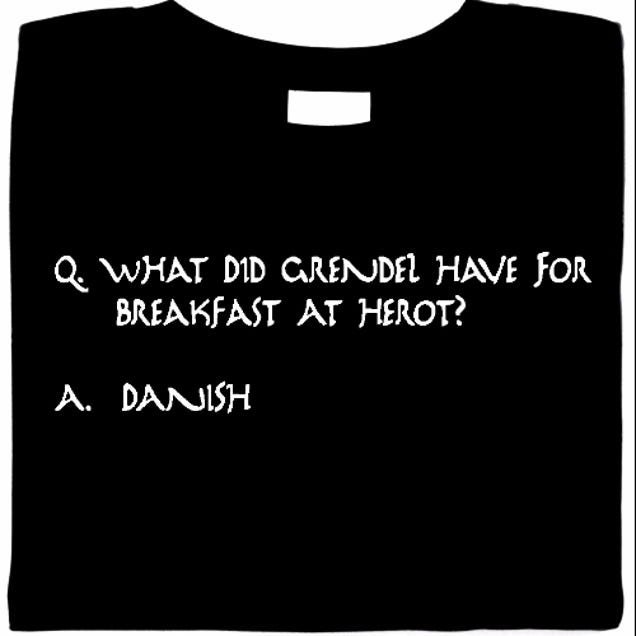

One

of the reading challenges of the epic Beowulf

is that the rules of the poem are always shifting. The most important “rule” is the

clear expectations of the good king. A

“good king” in the beginning of the epic is a man who rules by intimidation

(not fighting AS king) and who gives generously to the heroes closest to

him. The good king manages a community

and gives away gold.

Near

the end of the poem, Beowulf the king battles a dragon that has terrorized his

people. The poet next moves the

conversation to the emotional level and imagines not only the details of the

dragon’s hoard but also the dragon’s feelings towards his riches. Like all dragons, the dragon of this epic obsessively

values his immense hoard of treasure.

The poet calls this feeling in the dragon hord-wynne (hoard-joy) – the perverse affection for gold. Tolkien, in The Hobbit, calls this “dragon sickness.” This is the root of the dragon’s evil. “Good” behavior in this poem is signaled by

generosity, not hoarding.

Beowulf

manages to kill the dragon and acquire the dragon’s extensive wealth but dies after the fight. Beowulf utters his final

words and his speech is not a prayer, not an expression of gratitude to his

people, but rather a desire to see that “ancient gold” for which he has

died. We are left to wonder if the rules

for a “good king” still apply, whether Beowulf has redefined the notion of

“good king,” or whether he will use these new riches to reward his men. The poet does not make us wait long for an

answer. Near the end of the poem we are

told that the newfound material wealth is buried under ground, “as useless to

man as it ever was.” The rules are

changing.

He

behaves as a warrior when he should be behaving like a king, and the smoke of

his heroic funeral pyre is still rising when a nameless woman of his tribe

yells out a truth never heard in epic poetry.

The poet tells us that she:

. . . sang out in grief;

with hair unbound, she unburdened

herself

of her worst fears, a wild litany

of nightmare and lament, her nation

invaded,

enemies on the rampage, bodies in

piles,,

slavery and abasement. Heaven swallowed the smoke.

This is the price of

kings who forget themselves: nameless people suffer. This woman reminds us of the cost of

reckless leadership and a martial ethic that is less a solution and more a

never-ending circle of blood. The

progression of her nightmare is chronological and telling, from invasion to

rampage to body-count to slavery to the seeming indifference of heaven. How many women in Syria could utter these

exact words today?

I

often wish that this woman were given a name and, equally importantly, her own

words (rather than a paraphrase). But she

might be the most important nameless character in medieval literature for her

voice uniquely exposes a heroic code that is clearly losing ground. The rules of the poem and the world it

represents are changing. Gold is an ultimately empty rationale for risking

one’s life. Perhaps this

nameless woman, lost in the shadow of myth, reminds us that such “hoard-joy,”

such a blatant embrace of materialism, does not lead to immortality or even

short-term safety but rather the cycle of violence that provides the only stable rule

in the poem.