“A

little more than kin and less than kind.”

The

Elsinorian air around him full of poetic pronouncements,

straining against their iambic boxes

and his misguided promise to a ghost

in the woods.

He

never follows directions.

He

doesn’t know that he needs a clear tragic flaw.

He

never learns from Sophocles

how to model the evils of

overstepping his bounds.

He

has sworn away all bounds,

forever

living in the “goodly frame”

of the eloquent stage in his mind.

The

father whose airy armor demands revenge

is trumped by the un-poetic cruelty

of murder.

The

would-be father-in-law suffocates on the figurative air he can’t seem to

breath,

mocked by this Danish drop-out at

every turn.

The

young prince flees the love he desperately seeks.

He

is cruel to be kind to be cruel.

Best

friends gone, mother a betrayer or, worse, ignorant,

only the pedantic comrade left,

not even a shadow of the Protean hero

he follows so helplessly.

Pirates,

gravediggers, swordfights, staged murders,

secrets behind every curtain,

the readers’ eyes widen at every new

surprise.

Every

21st century teenager gets Hamlet,

the comedy, the sarcasm, the hatred

of boundaries,

the chameleon moodiness of him –

even though he is a 400-year-old ghost.

So

I smile when the workshop leader, addressing 30 teachers, pronounces,

“All stories fit into this 4 step

pattern,”

proudly pointing to a list of plot

devices on a large computer screen,

the bullet-listness of them

demanding self-evident agreement.

My fellow teachers are

actually writing this down.

I

imagine Hamlet sitting next to me, twirling his quill sarcastically, that smirk

on his face.

I

wonder how long it would have taken him to get up, push his chair in,

and walk out of the conference room

and into the lobby

for the illumination of a hot coffee

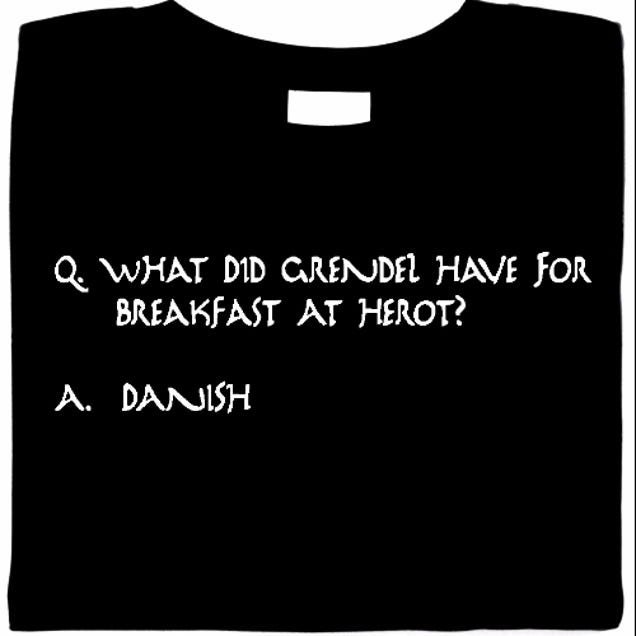

and an ironic Danish.